A week or two ago, I started reading The Nurture Assumption, a 1998 book about the [lack of] impact of parenting on children’s eventual personality. In the middle of the first chapter, there was the following:

Research done in the 1970s showed that you can get children to paint lots of pictures simply by rewarding them with candy or gold stars for doing so. But the rewards had a curious effect: as soon as they were discontinued, the children stopped painting pictures. They painted fewer pictures, once they were no longer being rewarded, than children who had never gotten any rewards for putting felt-tip pen to paper.

Although subsequent research has shown that it is possible to administer rewards without these negative aftereffects, the results are difficult to predict because they depend on subtle variations in the nature and timing of the reward and on the personality of the reward recipient.

I was surprised by this. This bit is not really key to the rest of the book, but I wasn’t aware that rewards could have such an effect, so I looked into the references. That sent me down a rabbit hole for a few days, learning about a decades-long academic spat in psychology that is still not totally resolved. Hang with me as I set the scene in the mid-late 1900s first and then take you through the years.

Here’s a handy link if you want to skip to a TLDR of the story followed by the conclusion.

Is intrinsic motivation real?

In the 1960s, the dominant theory of motivation was behaviorism, which at the time focused on how contingent rewards and punishments could be used to control behavior. There were different versions of behaviorism, but the general view was that all human behavior is shaped by external conditioning & reinforcement. Specifically, either certain neutral stimuli become associated with certain responses (Pavlov) or behaviors are shaped by external rewards/punishments.

Crucially, internal mental states are fully ignored and only observable behavior is considered. The mind is a black box where environmental stimuli are the input and behaviors are the output. In this model, theoretically one could use external rewards such as food or praise for specific behavior to condition someone into having a desired personality. You “could produce a doctor by rewarding a kid for bandaging a friend’s wounds.” Extrinsic motivation is all there is, and is powerful enough to achieve any desired long-term behavior or personality.

In 1971, Deci published The Effects of Externally Mediated Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation which asked questions like the below (emphasis mine):

If a boy who [already] enjoys mowing lawns begins to receive payment for the task, what will happen to his intrinsic motivation for performing this activity?

Or, if he [already] enjoys gardening and his parents seek to encourage this by providing verbal reinforcement and affection when he gardens, what will happen to his intrinsic motivation for gardening?

How do you measure something nebulous like intrinsic motivation?

Deci set up an experiment where each subject (college student) attended for 3 sessions on separate days, working on various configurations of a small puzzle toy1. The only difference between the experimental and the control group was that the experimental subjects were paid for successfully completing configurations within a time limit during the second session. Sessions 1 and 3 were unpaid for all subjects.

In the middle of each session, the experimenter left the room for 8 minutes on some pretext. At this point the student had gone through 2 of the 4 puzzle configurations that made up each session. The experimenter would tell the student they could do whatever they wanted while they were gone – work on the puzzle, read any of the magazines on the table, look around the room, etc. The measure of intrinsic motivation was the amount of time the student spent working on the puzzle, known as free-choice behavior. Free-choice behavior quickly became the standard for measuring intrinsic motivation in the field.

The control group students had ~no change in how much of their free-choice time they spent working on the puzzle across sessions 1, 2, or 3. Cool, they didn’t get bored.

The experimental group students, as you might expect, spent about a minute more of their free-choice time working on the puzzle in session 2 compared to session 1 – they were being paid in session 2 but not in session 1. But the experimental group also had a drop off of ~50 seconds in free-choice time spent on the puzzle in session 3 compared to session 1. Getting paid to solve the puzzle decreased their subsequent intrinsic motivation to work on it.

I’ll skip over the other two experiments and just state the other result of the paper, which is that verbal praise tended to increase subsequent intrinsic motivation, as measured by free-choice behavior.

Although this paper was seriously statistically under-powered, it produced surprising results that flew in the face of the behaviorism of the time, which would have predicted no change in the desire to perform a task after the monetary reward was removed. This undermining effect on intrinsic motivation has been replicated many times since.

Deci speculated that the reason for this undermining effect was that money is typically used to “control” or “buy off” people to perform certain behavior. When someone is already intrinsically motivated to do something, then gets paid for it, the extrinsic motivation of financial reward replaces some of their intrinsic motivation to do the activity. This explanation for the undermining effect is called overjustification, or “crowding out” of intrinsic motivation. But when verbal praise is given, it tends to be seen as less controlling & more as informational about a person’s competence, so it does not replace a person’s intrinsic motivation. The paper sowed the seeds for what’s known as Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET) and research on the undermining effect continued for the next 25 years. Your move, behaviorists.

Shots fired

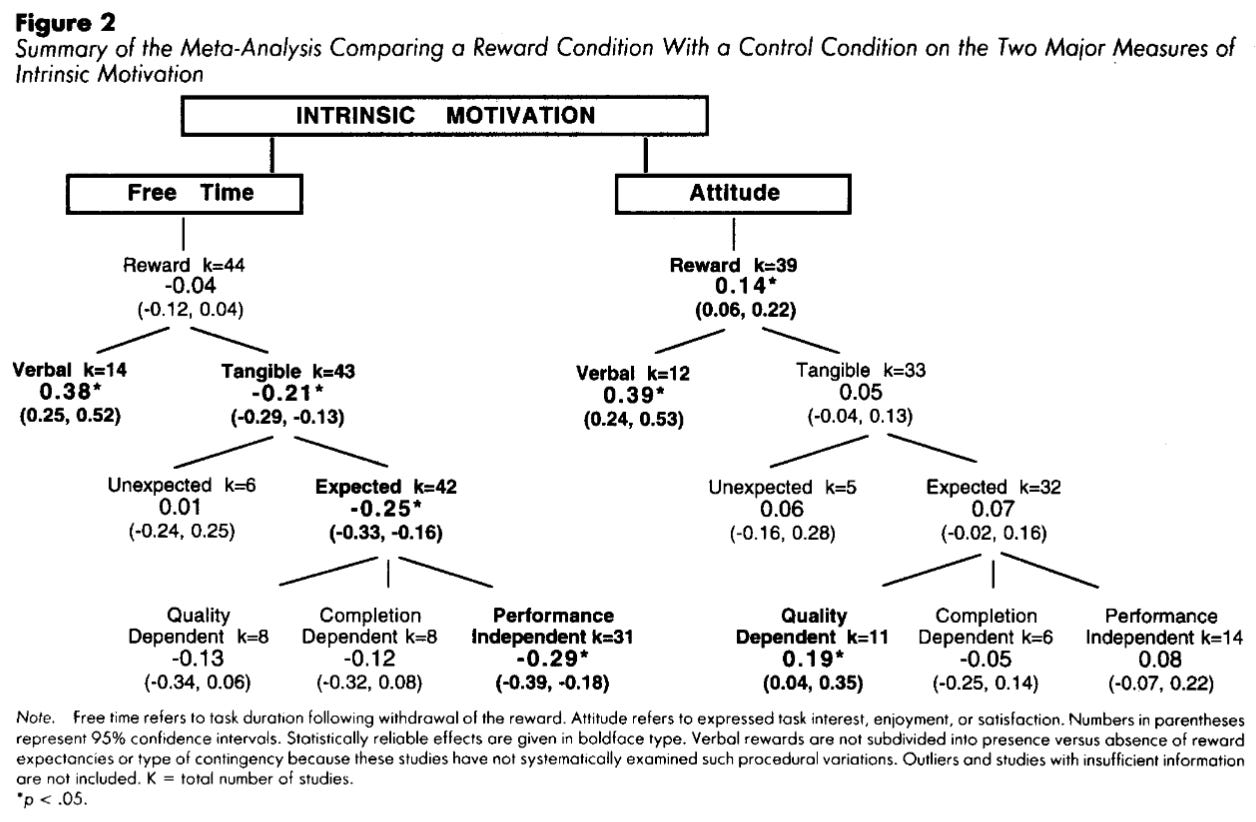

In 1996, a meta-analysis was published with the aggressive title Detrimental Effects of Rewards: Reality or Myth, by Eisenberger and Cameron. This was the first main challenge of the behaviorist theory of motivation to CET. It said that the undermining effect from tangible rewards only happens in specific conditions that can be easily avoided, and only performance-independent tangible rewards diminish intrinsic motivation with statistical significance. Here’s a diagram from the study with their results:

Of course our man Deci had to respond, along with Ryan and Koestner, with their own meta-analysis in 1999 titled A Meta-Analytic Review of Experiments Examining the Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation. Boring title, but the text included some sizzlers like:

Later, this meta-analysis was slightly redone, using the same studies and the same effects sizes but different groupings of studies, and was published by Eisenberger and Cameron (1996) in American Psychologist with very little methodological detail provided.

This paper further developed Cognitive Evaluation Theory with the idea that all rewards have conflicting effects; all are experienced partly as controlling (reducing autonomy) and partly as informational (affirming competence). Factors such as if the reward is expected or not, if it is contingent on engagement/completion/performance, the interpersonal context, etc all affect the balance of these conflicting effects.

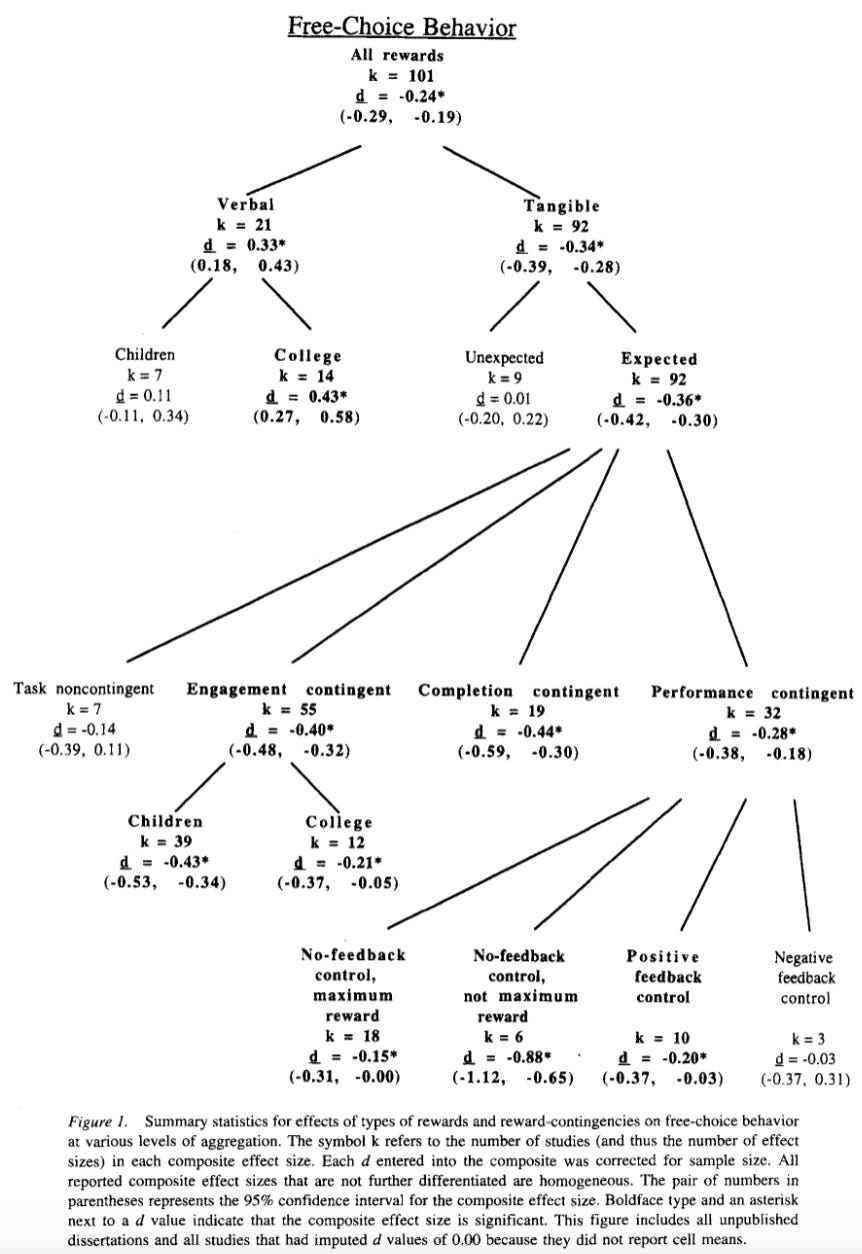

Their analysis supported their previous results & theory, showing that tangible rewards undermine intrinsic motivation, regardless of if they are dependent on engagement, completion, or performance. For performance-dependent rewards, people who got less than the maximum reward had the biggest drop off in intrinsic motivation, whereas people who get the max only had a minor drop off, if any. This supports Cognitive Evaluation Theory – getting less than the max reward is experienced as both controlling & also as negatively informational (failure of competence). Interestingly, tangible rewards tended to be more detrimental for children than college students, and verbal rewards tended to be less enhancing for children than college students. Children’s intrinsic motivation appeared to be more sensitive to undermining and less responsive to enhancement by verbal rewards than that of college students. Here’s their diagram:

But the behaviorists weren’t TKO’d yet. Next up from the studios of Cameron, Banko, and Pierce, yet another meta-analysis in 2001, Pervasive Negative Effects of Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation: The Myth Continues. Empire Strikes Back vibes. They end with this dramatic line:

Further research is necessary to show when and under what conditions rewards have positive effects on human behavior. What is clear at this time is that rewards do not inevitably have pervasive negative effects on intrinsic motivation. Nonetheless, the myth continues.

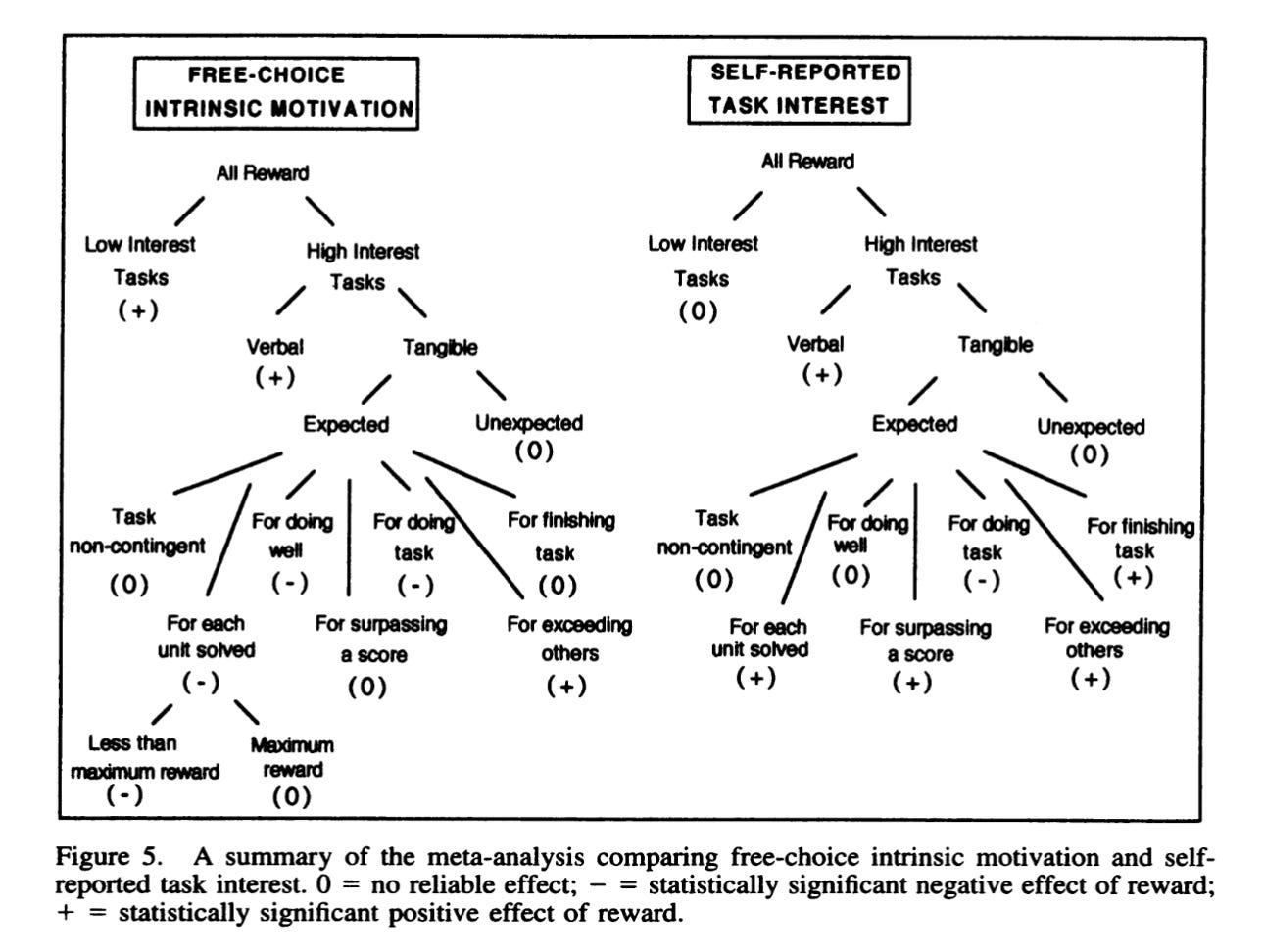

In the paper, they further break tasks down by high and low initial interest, and if the rewards are unexpected or expected. The results are best summarized in their diagram:

It might be a bit hard to tell, but the two sides are starting to converge. They always agreed that verbal rewards enhance intrinsic motivation & that tangible expected external rewards generally decrease it. The argument was always about what specific kinds of tangible rewards cause that decrease, and what kinds have no effect or enhance it. In 2001, they now also agreed that:

Engagement-contingent rewards decrease intrinsic motivation

Performance-contingent rewards generally decrease intrinsic motivation

The main thrust of this paper, and the last area of disagreement, is that performance rewards given for exceeding others can increase intrinsic motivation, and certain other kinds of performance-contingent rewards may not have any effect.

At this point things are starting to feel a bit p-hacky, even though these are meta-analyses. So you’ll be glad to hear that Deci, Koestner, and Ryan did yet another meta-analysis in 2001, with the passive-aggressive title Extrinsic Rewards and Intrinsic Motivation in Education: Reconsidered Once Again. No diagram, but they mostly reiterated the results from their 1999 paper, with a particular emphasis on how tangible external rewards are particularly undermining for school-aged children. They also reiterated that verbal rewards had no significant impact on intrinsic motivation for children.

TLDR

Skip ahead to the conclusion if you’ve already read the full story above.

The 2001 Deci et al paper has a wonderful recap of the history of this debate and why they felt the need to do yet another meta-analysis:

Gold stars, best-student awards, honor roles, pizzas for reading, and other reward-focused incentive systems have long been part of the currency of schools. Typically intended to motivate or reinforce student learning, such techniques have been widely advocated by some educators, although, in recent years, a few commentators have questioned their widespread use. The controversy has been prompted in part by psychological research that has demonstrated negative effects of extrinsic rewards on students' intrinsic motivation to learn. Some studies have suggested that, rather than always being positive motivators, rewards can at times undermine rather than enhance self-motivation, curiosity, interest, and persistence at learning tasks. Because of the widespread use of rewards in schools, a careful summary of reward effects on intrinsic motivation would seem to be of considerable importance for educators.

Accordingly, in the Fall 1994 issue of Review of Educational Research, Cameron and Pierce (1994) presented a meta-analysis of extrinsic reward effects on intrinsic motivation, concluding that, overall, rewards do not decrease intrinsic motivation. Implicitly acknowledging that intrinsic motivation is important for learning and adjustment in educational settings (see, e.g., Ryan & La Guardia, 1999), Cameron and Pierce nonetheless stated that "teachers have no reason to resist implementing incentive systems in the classroom" (p. 397). They also advocated abandoning Deci and Ryan's (1980) cognitive evaluation theory (CET), which had initially been formulated to explain both positive and negative reward effects on intrinsic motivation.

In the Spring 1996 issue of RER, three commentaries were published (Kohn, 1996; Lepper, Keavney, & Drake, 1996; Ryan & Deci, 1996) arguing that Cameron and Pierce's meta-analysis was flawed and that its conclusions were unwarranted. In that same issue, Cameron and Pierce (1996) responded to the commentaries by claiming that, rather than reanalyzing the data, the authors of the three commentaries had suggested "that the findings are invalid due to intentional bias, deliberate misrepresentation, and inept analysis" (p. 39). Subtitling their response "Protests and Accusations Do Not Alter the Results," Cameron and Pierce stated that any meaningful criticism of their article would have to include a reanalysis of the data. Subsequent to that interchange, Eisenberger and Cameron (1996) published an article in the American Psychologist summarizing the Cameron and Pierce (1994) meta-analysis and claiming that the so-called undermining of intrinsic motivation by extrinsic rewards, which they said had become accepted as reality, was in fact largely a myth.

We do not claim that there was "intentional bias" or "deliberate misrepresentation" in either the Cameron and Pierce (1994) meta-analysis or the Eisenberger and Cameron (1996) article, but we do believe, as Ryan and Deci argued in 1996, that Cameron and Pierce used some inappropriate procedures and made numerous errors in their meta-analysis. Therefore, because we believe the problems with their meta-analysis made their conclusions invalid, because we agree that a useful critique of their article must involve reanalysis of the data, and because the issue of reward effects on intrinsic motivation is extremely important for educators, we performed a new meta-analysis of reward effects on intrinsic motivation (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999).

So… where do we stand now?

The 5 years of 1996-2001 were the peak of this academic disagreement, at the end of which the disagreement was limited to a specific kind of performance-contingent reward. Many meta-analytic methodological differences were brought up and resolved, and the intrinsic motivation literature benefited a lot from the scientific drama.

I did not do a thorough review of papers after 2001, but my understanding is there have not been major changes since. Self-determination theory (of which Cognitive Evaluation Theory is a subset) has broadly superseded behaviorism. There were a couple interesting more recent papers that I’d like to mention, though:

Extrinsic Rewards Undermine Altruistic Tendencies in 20-Month-Olds, as the title implies, replicated the undermining effect in 20-month-old infants that were given material rewards (toy) for helping adults. Verbal rewards did not undermine intrinsic motivation. Wild.

Neural basis of the undermining effect of monetary reward on intrinsic motivation used an fMRI to directly measure the undermining effect as a decrease in activation of the reward network of the brain. The reward was performance-contingent, only given upon successful completion of a moderately challenging task.

Personally, I am pretty convinced the undermining/overjustification effect is real. If you give someone, especially young children, money for performing a task that they’re already motivated to do for its own sake, they will subsequently be less motivated to do so. Even if the reward is contingent on success or high performance, it still tends to decrease intrinsic motivation.

What are the implications of all of this on parenting2? I think the most useful part of this framework is that all rewards are experienced partly as controlling (reducing autonomy) and partly as informational (affirming competence). Making sure rewards are seen as affirming competence rather than trying to control behavior is key. More specifically:

If a kid is not interested in an activity already and you want them to do it, both verbal & tangible rewards are fine. Ideally the tangible rewards are performance/mastery based. They may gain some intrinsic motivation for the task eventually, in which case it’s probably best to phase out the rewards to avoid unintentionally undermining it.

If a kid is already interested in an activity

Avoid tangible rewards generally. Performance/mastery-based rewards are the least bad, but can still become a source of motivation that “crowds out” intrinsic motivation.

Verbal rewards & positive feedback are fine, and may help encourage intrinsic motivation, as long as they are not seen as trying to control behavior.

As kids get older, their intrinsic motivation appears to become relatively less undermine-able through tangible rewards and more enhance-able through verbal ones. Hard to say if that’s related to going through a school system which seems like a long exercise in replacing intrinsic with external motivation.

If my kid is already having a good time doing something by themself, I don’t plan to interfere at all. The ideal is them cultivating their intrinsic motivation and doing self-directed projects, with Kathy and me only helping to cultivate activities aligned with their interests as needed. I don’t plan to give them any tangible external reward (eg candy, screen time, whatever) or generally evaluate their performance when they are doing something they’re interested in doing already3. If they come to me and show me something they’ve drawn/built/whatever, I’ll give them positive feedback and encourage them, but I don’t plan to hover and give them unprompted positive feedback. The broader unifying idea is that I think a child from pretty much the very beginning is a separate individual with their own interests that they should pursue independently4.

Why did I go so deep into this rabbit hole? The nominal reason is because there are obvious implications to parenting and education. But the real reason is intrinsic motivation to learn about an interesting topic. Thankfully I’m not getting paid for it ;)

References

https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2019_RyanRyanDiDomencio_Deci1971.pdf

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14270444_Detrimental_Effects_of_Reward_Reality_or_Myth

Claude, when I had questions & for summarizing parts of papers

This was chosen because it seemed that most college students would be intrinsically motivated to do it. We’d probably use some mobile game nowadays.

Applications of self-determination theory to parenting: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/topics/application-parenting/

There’s a long obvious thread here re: traditional public school education and how grades etc is an external reward that almost certainly decreases intrinsic motivation. From the 2001 Deci paper:

Specifically, the results indicate that, rather than focusing on rewards for motivating students' learning, it is important to focus more on how to facilitate intrinsic motivation, for example, by beginning from the students' perspective to develop more interesting learning activities, to provide more choice, and to ensure that tasks are optimally challenging (e.g., Cordova & Lepper, 1996; Deci, Schwartz, et al., 1981; Harter, 1974; Reeve, Bolt, & Cai, 1999; Ryan & Grolnick, 1986; Zuckerman, Porac, Lathin, Smith, & Deci, 1978). In these ways, we will be more able to facilitate the type of motivation that has been found to promote creative task engagement (Amabile, 1982), cognitive flexibility (McGraw & McCullers, 1979), and conceptual understanding of learning activities (Benware & Deci, 1984; Grolnick & Ryan, 1987).

This aligns almost verbatim with the Montessori philosophy, which I strongly align with as well. That + homeschooling might honestly be the plan for the early years…

Broader than just the question here around rewards, I am a believer in self-determination theory, which posits that goal directed behaviors are driven by three innate psychological needs: autonomy (the need to feel ownership of one's behavior), competence (the need to produce desired outcomes and to experience mastery), and relatedness (the need to feel connected to others) in every human being.